Foreign Insulators

by Marilyn Albers

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", October 1994, page 13

U-1966, "THE PERFECT INSULATOR"

This unique insulator made its appearance at the Silver Anniversary National

Show held in Houston July 1-3,1994. It's not the sort of thing that would be

attractive to the average collector because its iron-clad body is an ugly gray,

and the iron hook prevents it from standing up by itself, so it is difficult to

display. But let me tell you, this grand old gentleman has a definite place in

the history of telegraphy . It is old and it is one of the rarest insulators in

existence.

It has no official marking of any kind, but handwritten in red pencil across

the iron shell is this inscription: "First Telegraph, Queensland, Australia

1864 P.M.G." The insulator was used on the telegraph line which ran between

Sydney, New South Wales, and Brisbane in Queensland. It was completed in 1861.

P.M.G. is for the Post Master -General' s Department, which operates the telephone and telegraph systems in Australia. The

1864 date may be when the insulator was installed, probably as a sturdy

replacement for an all white porcelain piece, which would have been an

attractive target for Aborigine arrows or rocks thrown by mischievous little

boys. That's close to a record for years of service!

Australia has always

depended on foreign trade. During the 19th century, it relied on British

industry for most manufactured items. Werner von Siemens of Hanover, Germany

(1816-1892), founded together with a skilled mechanic, J. F. Halske, the

electrical firm of Siemens & Halske for the manufacture of telegrahic

apparatus. This firm, under Siemens' guidance, became one of the most important

electrical undertakings in the world, with branches in different countries, of

which those of England and Russia were particularly important. Werner's brother

William represented the firm of Siemens and Halske in London, the branch from

which we may assume the U-1966 was ordered for use on the Sydney to Brisbane

telegraph line. In 1865 when the separate firm of Siemens Brothers & Co.

Ltd. of London was established, William became a partner and director. By 1910,

the company's catalog was offering several styles of iron-clad and iron-capped

insulators.

Was the U-1966 really the perfect insulator? Following are excerpts

taken from three different writings on the history of the electric telegraph.

Let's see what some of the experts had to say about it back in the mid 1860's

and early 1870's, plus some wise words from a knowledgeable collector of the

present time:

"THE TELEGRAPHER", JOURNAL OF ELECTRICAL PROGRESS,

August 31,1867

"Siemens' and Halske's celebrated insulator, which is extensively used in

all parts of the Old World, consists of a cast-iron bell with a flange attached,

by which it is screwed to the post. Inside the bell is cemented a white

porcelain cup, ribbed inside and out to give a good hold to the cement. Inside

this cup is cemented the wire hook, the stem of which is covered with vulcanized

rubber. The parts are put together while hot with a cement composed of sulphur

and oxide of iron".

"THE TELEGRAPH MANUAL" by T. P. Shaffner, 1859

"Until the year

1852, the insulators used on the (European) continent were made of glass,

porcelain, or burnt clay. At that time, Messrs. Siemens & Halske proposed

the bell-shaped insulator protected by an iron shield and first intended for use

in Russia. The insulators then in use were fragile and easily broken, even after

they had been placed upon the poles. Many would crack and absorb water, giving a

conductor to the electric current and greatly hindering the successful working

of the lines. It naturally became a matter of very great importance to remedy

the evil with all the possible speed. To this end, Messrs. Siemens and Halske,

gentleman distinguished for their great telegraphic skill, applied their

ingenious minds to the perfection of an insulator that would more substantially subserve the purpose of the

telegraphic service. After various improvements in the form and insulating

properties of materials, and their combinations, those hereinafter mentioned

were tried and proved eminently successful. It has been estimated that at least

twenty-five per cent of the former insulators had to be annually renewed. This

breakage occasioned not only a great expense for their replacement with new

insulators, but heavy losses were sustained by the lines not being able to

transmit the necessary business of the government, nor that which was offered on

commercial affairs.

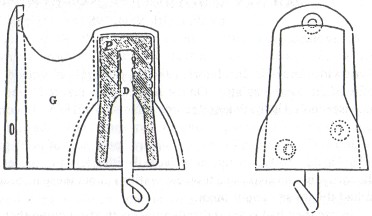

Figure 61.

Figure 61 represents the common insulator now used on telegraph lines in

Prussia, Russia and Germany. Letter G is a cast-iron body. P

is the china, glass

or porcelain insulator fitted into the iron bell. D is the wire supporter

fastened into the insulating material. The insulator P and the iron supporter

D

are fastened in their respective places by a mixture of sulphur and colcathar,

which makes a good cement, and firmly binds the respective parts to each other.

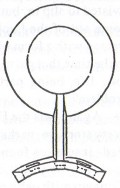

The views, Figures 61 and 62, are sufficient to represent its construction

without further explanation. Figure 62 represents the top view and the curvature

that fits to the post. The nail or screw holes are marked by dotted lines.

Figure 62.

Wherever these insulators have been employed the telegraph worked with the most

complete success. The insulators have proved to be the most perfect as to

insulation and permanency used on the continental telegraph lines. . The china P

securely insulates the iron supporter D from the cast-iron bell G, and the

flange mouths of G and P prevent the collection of water whether in times of rain

or of fog. The insulator cannot be broken from the post, and it is capable of

sustaining a far greater weight than the wire which it suspends. It comports

fully with the otherwise substantial structure of those northern lines."

"THE HISTORY AND PROGRESS OF THE ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH"

by Robert

Sabine, 1872, London

The author described the Siemens and Halske iron-clad

insulator as the first of its kind to be made and while it was the strongest, it

was also the most expensive. He felt the insulators were "a little heavy, but

that their superior solidarity and insulation were ample compensation, the iron

cap forming at once a perfect protection against injury and a screen against the

deposit of dew on the porcelain". He pointed out that sometimes the

porcelain cup was replaced by a cup of vulcanite.

"RAIL WAY AND OTHER RARE

INSULATORS"

by W. Keith Neal, 1987

An example of U-1966 is included in the

W. Keith Neal collection of Guernsey, Channel Islands. In fact, the scale

drawing you may have seen in "Worldwide Porcelain Insulators, 1986

Supplement" was made from a shadow profile of this very insulator. On the

iron cover is marked 'Siemens Patent 1', which is recorded in the Patent Records

as No. 464 of 1863. In contrast to figure 61, which shows a curved flange to fit

a round pole, the flange on Keith's insulator is flat so it can fasten to a

square baulk pole of pitch pine, typical of England in the 1880' s, or any flat

surface. Keith prized this piece highly because of its rarity, but he also had a

few reservations about these insulators in general and had this to say about

them:

"In use they had several disadvantages, the first being that they

attracted spiders who spun webs in the darkened part inside, which in turn

attracted damp and caused at least partial failure of insulation. They also

allowed smoke deposit to build up, without the benefit of rain to wash it clean.

The iron cover being made so close a fit to the porcelain it protected, the

carbon deposit thus caused further failure being a conductor. The first

iron-clad with a hook and no 'windows' was the worst offender and it was rapidly

supplanted by the model shown in 'Searching for Railway Telegraph Insulators'

(W. Keith Neal),

Figure 48. (This would be U-1965A, an ironclad insulator with windows --

Marilyn).

The iron rod in the center (of U-1966) is completely bound with gutta

percha forming at its base a hook, which is cleverly made so that when the line

is slack it can be twisted to slip in, but when the line is strained up it

cannot come out of the hook. The iron covers

themselves were treated with a form of rust repellent which appears to

have been effective prior to the time that galvanizing came into general use.

Iron-clad insulators had a long life, being particularly useful where persistent

stone throwing was a problem".

Again, was the U-1966 a perfect insulator?

There are always two sides to every story, so perhaps you would like to decide

for yourself. Siemens' ironclad insulators found their way to many parts of the

world. Keep your eyes open, maybe you'll come across one of them. Many, many

thanks to Ray Klingensmith, who provided most of the information for this

article.

|